Every businessperson with a vision of where they are going, and specific strategies and goals to get there, will face obstacles or barriers that hinder them from achieving success. Frequently, when confronted with solving problems or making improvements, business owners or managers feel overwhelmed. They lack the time, money, or resources to correct the problems they are experiencing. They often feel like their hands are tied, and they don’t know where to begin.

You can start by confronting the brutal facts about your business operations—the problems that are staring you in the face. For example: from customer or employee complaints, discouraging financial or performance reports, or just plain gut-level frustration, you have a general idea of your weaknesses and challenges. As discussed earlier, these symptoms are the result of unhealthy and under-performing business systems and processes.

In 1984, Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt, in his book The Goal, introduced the Theory of Constraints (TOC), a management philosophy based upon the application of logic and scientific principles, to help organizations achieve their goals. The principles of TOC will provide you the shortest distance between two points—where you currently are, and where you want to go.

What Is the Theory of Constraints?

The Theory of Constraints is based upon the assertion that: “Every real system, such as a business, must have within it at least one constraint (limiting factor). If this were not the case then the system could produce unlimited amounts of whatever it was striving for, profit in the case of a business. . .” (Dr. Eli Goldratt).

In other words, every business operation has something inhibiting it from reaching its full potential. Some condition exists that limits sales or production output. This limit or constraint determines the maximum capacity of the system. By removing or improving the single constraint, the system is elevated to a higher level of performance.

Below are six types of constraints that can hold back an organization. The solution to your problems can be found in any or all of them; some may overlap.

- A Logical Constraint – Faulty thinking or assumptions can block success (e.g., believing people are the problem when ineffective systems—hiring, training, and so forth—are the real problem).

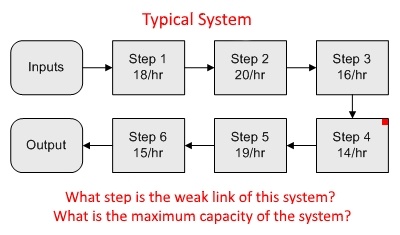

- A Process Constraint – The output of work processes is reduced by a weak-link or bottleneck in the process (e.g., work piled up in an in-basket; inventory waiting to be processed).

- A Physical Constraint – Physical components of a process often have limitations (e.g., the capacity of a machine; available space or time; capability of a person; physical obstacles such as clutter or travel distance, and so forth).

- A Self-inflicted Constraint – A company’s culture, rules, or policies can have a detrimental effect on results (e.g., lack of accountability, not hiring older people; sticking with the “sacred cows” of work practices).

- A Personal Constraint – Personal traits of an owner or manager can hinder performance (e.g., disorganization, procrastination, perfectionism, indecision, fear, incompetence, lack of time, or failure to face problems). Do you have any beliefs or behaviors that are holding back your business?

- An External/Market Constraint – Obstacles can exist that you have no control over (e.g., market size; customer attitudes; competition; the economy). You can often adapt to these external constraints over time by adjusting your business strategy.

As with a medical diagnosis, the symptoms of a business problem don’t always point directly to the cause of the problem. In fact, most of the time, the problem you experience is not the real constraint. Just as a cough is only a symptom of an unhealthy system within the body, the pain or frustration you feel about your business is likely the effect of a deeper problem. Some constraints (e.g., physical) are more apparent than other constraints (e.g., logical).

Consider this: While there can be a variety of problems within a business system, only one step of the process at a time is the constraint on the entire system—the weak link and true cause of restricted output.

You can only improve the results or output of that system by eliminating the weak link or elevating its performance. Time, effort, and money spent to strengthen the other links in the chain—the other steps in the process—will not improve the system output. The weak link governs the performance of the whole system!

(Answers: Step 4; 14 per hour)

Once you have strengthened or elevated the weak link, another link or step in the process becomes the weakest and may deserve your attention. Thus, by always focusing efforts on the weakest part of the system, you get the maximum benefit from your business improvement efforts.

Because only a few core systems or processes drive your business results—and each has just one constraint at a time—you can now focus your energy on the few problems that really matter the most. Make the necessary improvements and then tackle a new constraint. Watch your business take off!

Theory of Constraints: Performance = Full Potential – Constraints

Throughput

The Theory of Constraints assumes that a system has a single productivity goal. The challenge is to increase the output, or “throughput” of the system by managing the constraint that blocks your ability to reach that goal.

For example, the throughput of a marketing and sales process is measured by the dollar-value of orders written. The throughput of a production system is the dollar-value of products shipped. For a business as a whole, the measurement of throughput is the final cash collected from the sale of its products or services.

Many company owners mistakenly think they need to optimize all of their business systems and processes (logic constraint). They often measure individual processes and reward performance independent of overall business results.

Surprisingly, the improvements in quality or efficiency, as important as they are, do not always lead to a corresponding improvement in total throughput. In fact, an optimized system or process can create a negative effect on the next system in a line by overwhelming it with too many inputs.

Improving any but the weakest step within a process creates excess output that piles up in front of the weak step, often called a bottleneck. Bad things happen when work piles up, when you overfeed a process. Don’t create any more inventory or work-in-process than is necessary to maximize throughput!

Remember: The key is not just to eliminate the bottleneck-step of a particular system, but to elevate any complete system or business activity that constrains the throughput of the entire business. All of your core business systems and processes must work in synchronization to achieve the optimum result. While efficiency and cost-cutting are important, the best measurement of real improvement is increased throughput—revenue and profit.

In my experience with small businesses, insufficient sales are usually the major constraint on the throughput of the business. No matter how efficient the operation, without a steady flow of sales into the pipeline, the output is always disappointing.

By the way, your cost of goods plus overhead expenses create a monthly sales break-even point for your business. Throughput should cover those costs as early in the month as possible. You only make a profit on orders shipped after you reach the break-even point!

TOC in Action

Kid’s Korner manufactures and distributes a unique line of children’s furniture and accessories through five retail stores located in shopping malls. Owners want to double annual sales from three to six million dollars without the cost of adding more stores. They also want to preserve the margin in their product by staying in the retail market. They decide to put their available resources into Internet marketing.

The first constraint the owners face is that not enough people visit their sorry website. They hire a person skilled at search engine optimization (SEO) and Google Ads to improve online traffic. With more people coming to the site, their constraint is now the low percentage of visitors who become paying customers.

The owners hire a professional copywriter to improve their message and add an irresistible offer of free shipping. To their surprise and excitement, product sales start to take off! Sales throughput, however, does not increase as expected. They soon discover the next constraint, their inability to fulfill all the orders on a timely basis. The company adds another person to their bottleneck shipping department, and the problem is solved; sales throughput goes up.

The results from the website continue to exceed the owner’s expectations, but now they can’t keep all of their products in stock—a new constraint to overcome. For example, they have a line of lamps that come in twelve different styles. Production is hampered because they must break down and set up the production line for each style.

A review of sales data shows that four lamp models account for 75% of their lamp revenue (see 80-20 Rule). They make a difficult decision to trim the models to four. A miracle occurs! While they lose a few sales, production is much more efficient and the throughput on lamps dramatically increases—overall business throughput also jumps.

Lamp production has improved enough that sales again become the constraint for this item. The owners decide to take advantage of the productivity and warehouse the excess inventory. This proves to be a costly decision. It ties up needed cash. Demand drops drastically on one of the stocked lamps, and a production flaw, not caught during the inventory buildup, causes a significant amount of rejects and waste.

The owners revise their strategy and begin to pace lamp production with sales—no inventory buildup of potentially obsolete items, no cash sitting on shelves, no hidden production flaws. They discover that more profit is made when sales and production flow through an evenly paced business system.

By applying the Theory of Constraints, the owners of Kid’s Korner focused on the critical systems and processes that would increase throughput and help them reach their six-million-dollar goal.

While you may have a different business model, these TOC principles also pertain to your company.

Now, go find the constraints—weak links, bottlenecks, obstacles—that are hindering the throughput of your business!